In June, I finished our initial research project fieldwork, Electrolysis of Seawater: Effects of Low-Voltage on Alkalinity and Other Critical Parameters Required for Coral Reef Resiliency at Hanalei Bay in Kaua’i. I’m working on the research paper to cover all the results, but here’s the story of how it went.

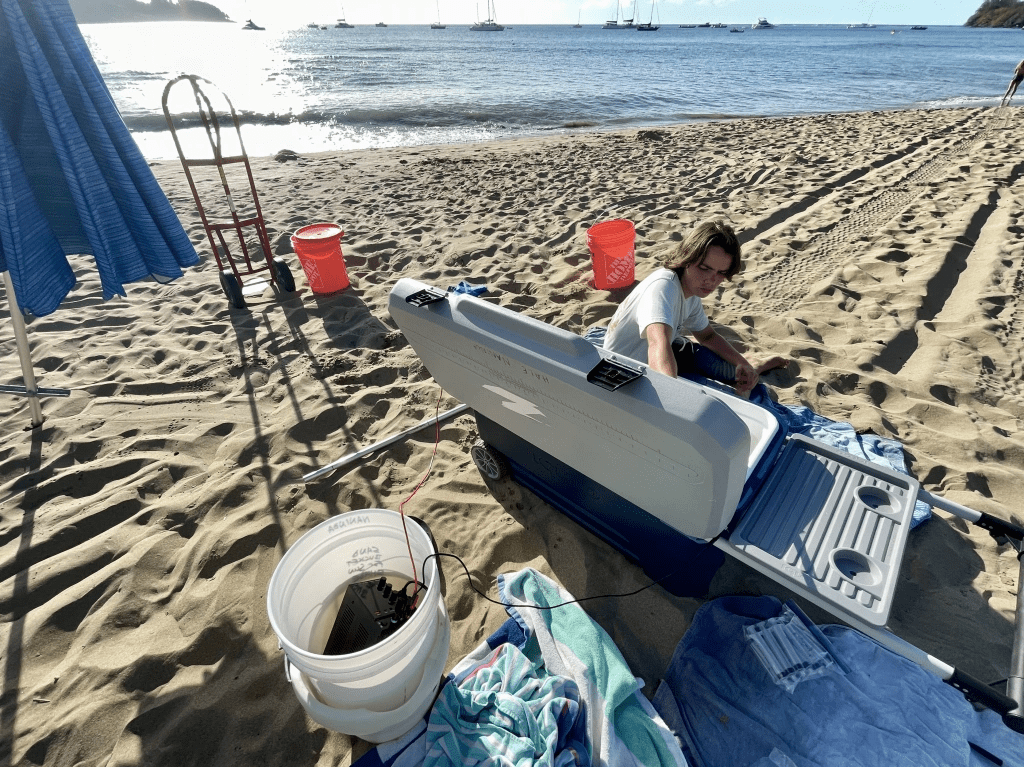

We brought most of our scientific equipment with us from California – the testing gear and reagents, power supply, cathode and anode, etc. – but for the experimental chambers, we got a large cooler and five-gallon Home Depot buckets in Hawai’i.

Since each experiment required about 25 gallons of seawater (over 200 pounds), we set up on the beach to make it easier to carry the water. We did it in the evening so there were fewer crowds and less wind. The local canoe club also took advantage of the pleasant marine conditions.

The Experiments

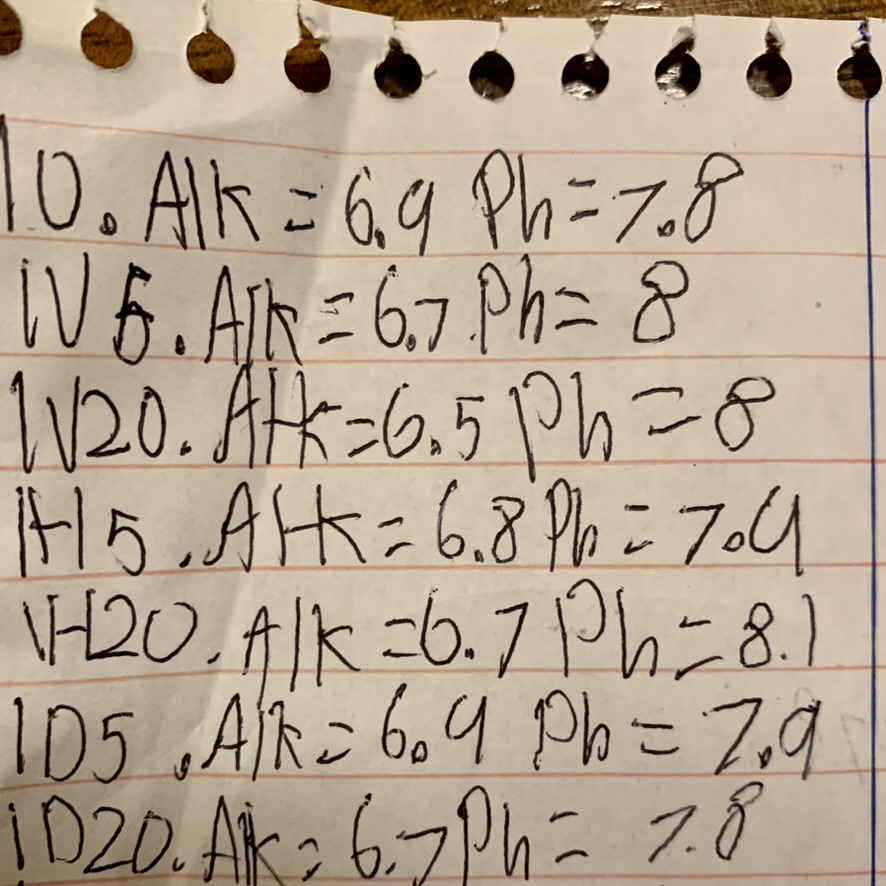

The first set of experiments on June 7th went smoothly. We filled the large cooler with fresh seawater for each experiment, and I took 8 samples of seawater at different distances from the cathode for two experiments at different voltages.

The next set of experiments were to run for longer periods of time (several hours to several days) to simulate our eventual experiments with live coral in aquariums, so we had to lug a large amount of seawater back from the beach. That was a lot of work, and the lifeguards were a bit curious. They were the first of many people wondering what we were up to.

The next day on June 8th, I used several Hanna Instruments photometers to test alkalinity and pH to see if the electrolysis at the cathode had created better ocean chemistry conditions and chlorine concentrations to see if electrolysis at the anode had created harmful dissolved chlorine in our test chamber.

An Important Experimental Result

This is when we got an important experimental result – too much chlorine.

Home aquarists know that chlorine is extremely toxic and often lethal to fish and marine invertebrates even at the low levels used for sanitation in drinking water. Most drinking water has 1 to 2 ppm of chlorine, which is still safe for humans. However, chlorine is lethal to fish at 10% of that level, or 0.1 to 0.3 ppm, and most aquarists aim to keep their chlorine at 0.001 to 0.003 ppm for optimal long-term marine health, or 1/1000th of the level in drinking water.

I knew that seawater electrolysis would generate chlorine gas, but we thought we could minimize the effects by running the experiments for only a few minutes at very low voltage and current. Also, the chemistry of chlorine in seawater is extremely complex with many ways the chlorine might be neutralized, and there are many examples of saltwater electrolysis being used to improve reef health in the open ocean, so we thought it might work even in an enclosed experiment. Finding that out was one of the reasons I did the experiment.

We suspected there was still a problem even while the experiments were running. First, we noticed that the copepods that had been swept up in our seawater samples were actively darting away from the anode, which was generating chlorine gas, and toward the iron bars of the cathode where the water chemistry was healthier. Second, after the experiments were complete, the seawater samples had a very slight bleach smell, which was not a good sign. Finally, after the overnight experiment all of the copepods were dead, huddled beneath the cathode as if they were trying to protect themselves from the chlorine.

However, when I tested the samples for chlorine the next day, all of the chlorine had reacted and it was no longer present in testable amounts. Since I knew there was chlorine being dissolved into the water while the electrolysis was running, we added a new experiment protocol that we called a “blitz test” where we ran a very short experiment in a 5-gallon bucket, and I immediately tested the sample for chlorine. As feared, the sample showed 2.78 ppm of chlorine which is safe for humans but 10 to 1000 times above the toxicity level for marine life.

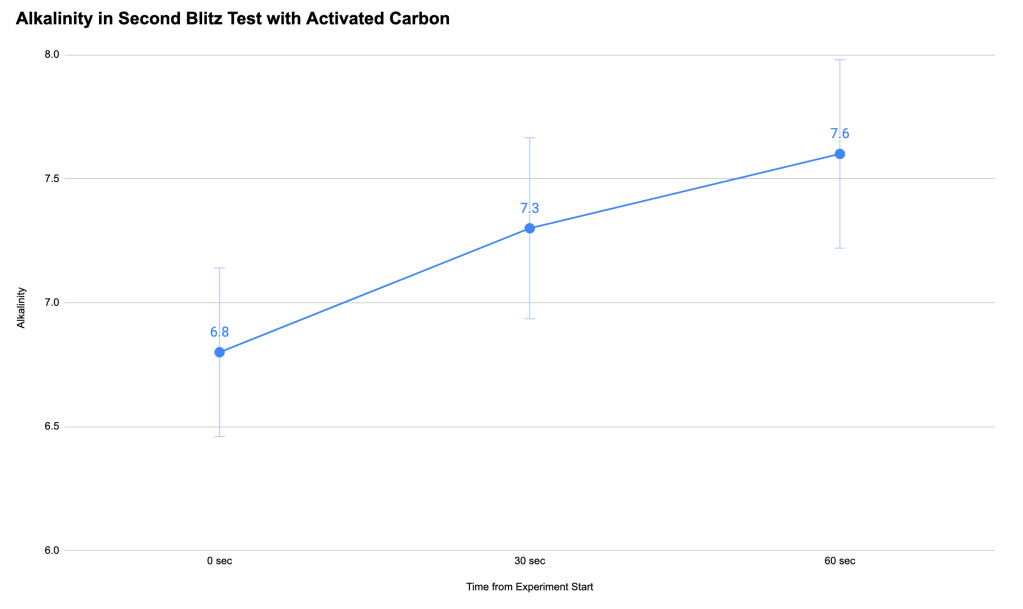

We had anticipated that chlorine would be a problem, so we had activated carbon filters from my home aquariums on hand to try to neutralize the chlorine generated at the anode during the experiment. We ran a second blitz test with the anode wrapped in activated carbon and were very happy to see that it worked to keep the chlorine below detectable levels. Even better, we also found that the experiment did in fact increase the alkalinity of the seawater near the cathode, potentially generating a healthier local environment for coral growth.

After taking some time off for great snorkeling, scuba diving, surfing and sailing, I did one last experiment on the beach. The experiment was the same as our first beach experiments, only this time we wrapped the platinum-coated titanium anode in activated carbon. This successfully eliminated the dissolved chlorine problem.

Moving on to the Next Phase

Because there was a large canoe regatta that day, I also got a little practice talking with the public about our research and how we hope to make more resilient reefs through electrolysis. I still have some work to do on that front.

Next, I’m moving on to writing up all the experimental results and setting up our next phase of research trying to apply what we’ve learned to an experimental aquarium set up to measure the effects of electrolysis on coral resiliency. More on that soon.

Leave a reply to Ground-Breaking 17-Month Study Overcomes Barriers To Enhanced Coral Growth And Resilience Using Seawater Electrolysis In Closed Aquariums – Resilient Reef Research Cancel reply