In my study, I set out to explore how low-voltage electrolysis impacts coral growth and resilience in a closed system. The complexity of electrolysis in seawater systems, the sensitivity of coral to changing water chemistry, and the relative scarcity of previous research required an iterative experimental approach that spanned 17-months of work, as described below. Finally, after failing many times and giving up all hope, I found a way forward and achieved successful results. I am publishing them now so they can form the basis for exciting future research.

First Experiment – Closed Seawater Chambers

In the first phase of the study, I set out to explore how low-voltage electrolysis impacts seawater alkalinity in a closed system.

Experimental Setup & Results

I performed a series of tests in Hawai’i using fresh ocean water and 5- and 25-gallon closed experimental chambers. All experiments were performed outside on the beach to ensure adequate ventilation. The initial observations can be found here, and final analysis is here.

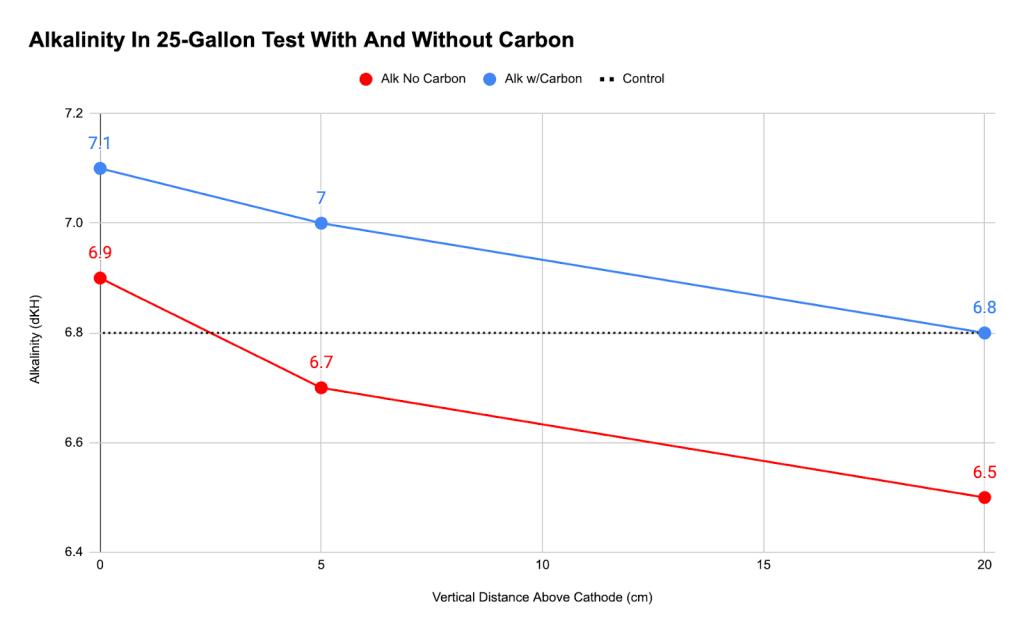

- Used a 25-gal cooler filled with seawater to measure how water chemistry varied by distance from the cathode immediately after energizing the system. I observed that the alkalinity decreased from 7.0 to 6.7 dkH. There was a strong smell of chlorine, and a subsequent free chlorine test was off the charts. I also saw free-swimming copepods actively swimming away from the anode to hover above the cathode.

- Used a 25-gallon container to run an overnight experiment to test longer-term chemical changes. The cathode had a visible hard film of calcium carbonate deposition. I also found a dozen dead copepods beneath the cathode where they had tried to shelter from the harsh water chemistry in the relatively more hospitable region of the cathode.

- Used a 5-gallon container to do a 5-second “blitz” test to measure the chemical changes caused by higher voltage and current (17 volts and 10 amps). That water had a free chlorine concentration of 2.78 ppm and an alkalinity of 0, indicating that chlorine in the water causes a drastic decrease in alkalinity.

- Used a 5-gallon container to test the effectiveness of carbon-wrapped anode to eliminate chlorine in a closed system. I observed an active stream of chlorine gas bubbles from the anode, but subsequent tests of free chlorine were zero – a successful test of activated carbon to remove chlorine produced by electrolysis.

- Used a 25-gal cooler filled with seawater and a carbon-wrapped anode to measure how water chemistry varied by distance from the cathode immediately after energizing the system. The alkalinity and pH values showed a clear gradient, increasing near the cathode as hoped.

Discussion

Initially, I expected electrolysis to increase alkalinity, but my first experiments showed the opposite—alkalinity actually decreased. This unexpected result led me to hypothesize that chlorine produced during electrolysis was reacting with carbonate ions, lowering the alkalinity. To test this, I conducted experiments using activated carbon to adsorb the chlorine, and I observed that alkalinity increased, confirming our hypothesis.

I also discovered that alkalinity is highest near the cathode, demonstrating that the cathode directly boosts local alkalinity, and that naturally occuring copepods sought out the relative protection of the water chemistry near the cathode. Interestingly, pH measurements indicated that electrolysis doesn’t significantly affect pH, regardless of the presence of activated carbon. In my high-amperage short-length experiments, I found that chlorine drastically reduces alkalinity, but this effect can be entirely neutralized by using activated carbon to adsorb the chlorine, allowing alkalinity to rise rapidly.

These results validate my updated hypothesis: Electrolysis can indeed increase seawater alkalinity in a closed system, but only if chlorine is properly managed. The success of activated carbon in controlling chlorine production in my experiments opened the door for future research into optimizing this process, particularly in applications like enhancing coral growth. These early findings provide a crucial step forward in understanding how to use electrolysis effectively in closed systems.

Second Experiment – Closed Marine Aquarium With Unseasoned Carbon

This was the first experiment run with live coral and the first application of my experimental setup. The explanation of that setup can be found here.It revolves around a control and an experimental tank. To create the tanks, I acquired four 26-gallon plastic tubs and drilled two holes in their ends. Using PVC pipes, I then connected two pairs of tanks using two PVC pipes for each pair. The goal was to limit the amount of water flow between the anode and the cathode to prevent the harmful compounds created by the anode from reaching the coral.

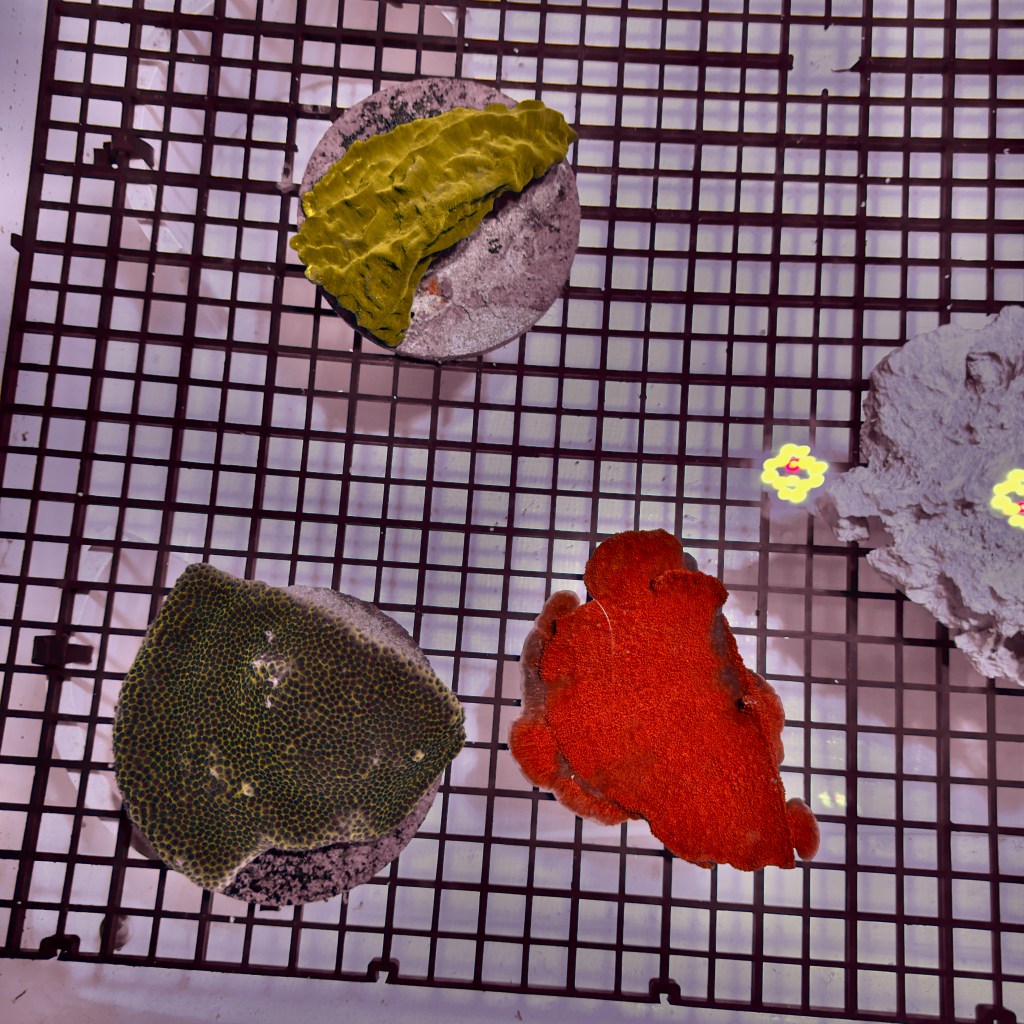

The main innovation is the 2-gallon perforated bucket filled with carbon surrounding the anode. The same amount of carbon was placed in both the experimental and the control tank to reduce variables. The carbon in the control tank had been sitting in salt water for 1 week. Importantly,the carbon in the experimental tank was added on the day of the experiment. Over the previous week, I had run successful tests of the carbon’s chlorine-adsorbing effectiveness at very high amperages. I predicted the high dosage of chlorine would harm the adsorptive capability of the carbon, so I replaced the carbon to be safe. This resulted in a critical accidental discovery. Every coral was weighed and photographed before being placed into each tank, as well as being carefully acclimated and treated with CoralRX to reduce stress. The alkalinities, pH, temperature, salinity, magnesium, and calcium were stable between the two tanks before starting electrolysis.

The next morning, the corals in the control tank remained healthy, but every coral in the experimental tank had died. I measured all of those same parameters, and they remained in a healthy range. The alkalinity of the experimental tank had fallen slightly due to the electrolysis, but not enough to harm to the coral. Additionally, I sent the water in the experimental tank to an Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Spectroscopy testing facility to measure all atomic components of the water, which detected nothing extreme enough to explain such mass death. That essentially ruled out electrolysis as the cause of death, so the next thing that was out of the ordinary enough to cause such sudden death was the brand-new activated carbon. Activated carbon is supposed to be harmless in marine aquariums, and is regularly used by aquarists to remove volatile organic compounds and toxic waste products. However, it is never added to aquariums in such vast quantities as I used. I used 5 kilograms of brand-new carbon in 45 gallons of water, which was guaranteed to change the water in some drastic way.

That theory was backed up by the lack of death in the control tank, which had the same amount of carbon, but that carbon had been seasoned in saltwater for a week with active mechanical and biological filtration running, so any major transient effects would have happened before the coral was added. Perhaps the brand-new carbon was still covered in micro granules of activated carbon, which entered the water column and harmed the coral, or perhaps the huge reactive surface area of the activated carbon, over 160 million square feet of activated carbon surface in a relatively small 45-gallon tank, caused a cascade of other damaging chemical reactions in the complex living seawater solution. I do not know exactly why the addition of brand-new carbon caused such disastrous results, but I did not make that same mistake in the next experiment.

Third Experiment – Closed Marine Aquarium With Seasoned Carbon

The third experiment was the culmination of everything I had learned so far. The experimental setup was similar to the first experiment. However, this time, I let the activated carbon surrounding the anode sit in the water for 1 week before changing out that water. I also removed the 5kg of carbon from the control tank, as I realized that having it there did not make it an accurate control. This experiment aimed to fix all of the shortcomings that I had detected before, and hopefully, I could finally get some data on the efficacy of electrolysis. However, as before, it did not go to plan. A couple of days after turning on the electrolysis, the corals in the experimental tank started to look unhealthy, and a few specimens began to bleach. At the time, this was a devastating result, but looking back, I see great progress. I had progressed from keeping the corals alive for a few hours to a few days. I pulled the corals from the experimental tank before they died and kept them in the control tank so they could recover.

Now I was faced with a new conundrum, what went wrong this time? Given my experiences thus far, that was a question I had become very good at answering, so it only took a few days of research to pin it down. Somehow, the carbon surrounding the anode was acting as an electrode in the system. When carbon acts as an electrode, it deionizes saline water. In this case, it pulled the chlorine and sodium molecules out of the water and changed their form. When I read that research, I knew it must be the answer. I sent the water to an ICP testing facility and found that the chlorine levels had dropped by 23.6% and the sodium levels had dropped by 18%. The difference between the two values was likely do to gaseous chloring bubbling off from the anode, while other chemical reactions in the carbon anode were capturing the rest of the chlorine and sodium at far higher rates than I expected.

That major finding made me realize I had to completely rethink my approach. I had two things to fix before the next experiment: keep the carbon from contacting the anode, and maintain holistic water chemistry.

Fourth Experiment – Closed Marine Aquarium With Seasoned Carbon, Complete Water Changes, and a Filter Floss Barrier Between the Anode and Carbon

Like the others, the fourth experiment was the culmination of the problems faced by the previous experiments. I learned two main lessons from the third experiment: the carbon cannot contact the anode, and something must be done to replace the dissolved compounds changed by the electrolysis.

The easiest fix was preventing the carbon from acting as an electrode. I solved that by surrounding the anode with a thick layer of filter floss to keep the ruthenium-coated titanium anode from transferring electrons through the carbon.

I also realized that my method of dosing calcium, magnesium, and alkalinity to maintain healthy water chemistry was insufficient. The chemical changes enacted by electrolysis were too sweeping and significant for me to replace by dosing those three compounds. In the open ocean, electrolysis works because tidal and oceanic the currents constantly refresh the water surrounding the corals. I obviously cannot achieve that same effect without a wet lab, but the next best thing is frequent water changes. I decided that full water changes would be done every 5 days in the experimental tank.

Ideally, those two changes would solve all previous problems.

This time, the corals managed to survive a full 2 weeks before they started to bleach and I decided to terminate the experiment and pull them from the experimental tank. They lived over a hundred times longer than my previous attempt. Clearly, the filter floss was working, but something was still happening. It was then I took another hard look at the equation of electrolysis. Although I have not found every reaction that results from electrolysis, I know it is incredibly extensive. I had hoped to combat that with the water changes, but it appeared every 5 days was not frequent enough. Mixing and replacing that much salt water is very resource intensive, and a water change every 5 days was already extreme. If more water changes were required, was it even worth it? I spent a while pondering that hard truth and had given up at one point. What if the reactions were simply too sweeping, and electrolysis wasn’t feasible in a closed environment?

Then, when all hope was lost, I took another look at the original patent that Thomas Goreau wrote when he discovered the coral-growing power of seawater electrolysis. In one of his experiments, he found that similar positive results were achieved when the electrolysis was only run for a short period, usually about an hour a day. I then resolved to run another experiment putting that into effect. If it worked, it could be a huge advance – only one hour a day means significantly fewer harmful compounds would be created, meaning the carbon would last longer, and water changes could be far less frequent. I finally had hope again.

Fifth Experiment – Closed Marine Aquarium With Seasoned Carbon, Complete Water Changes and Metered Electrolysis

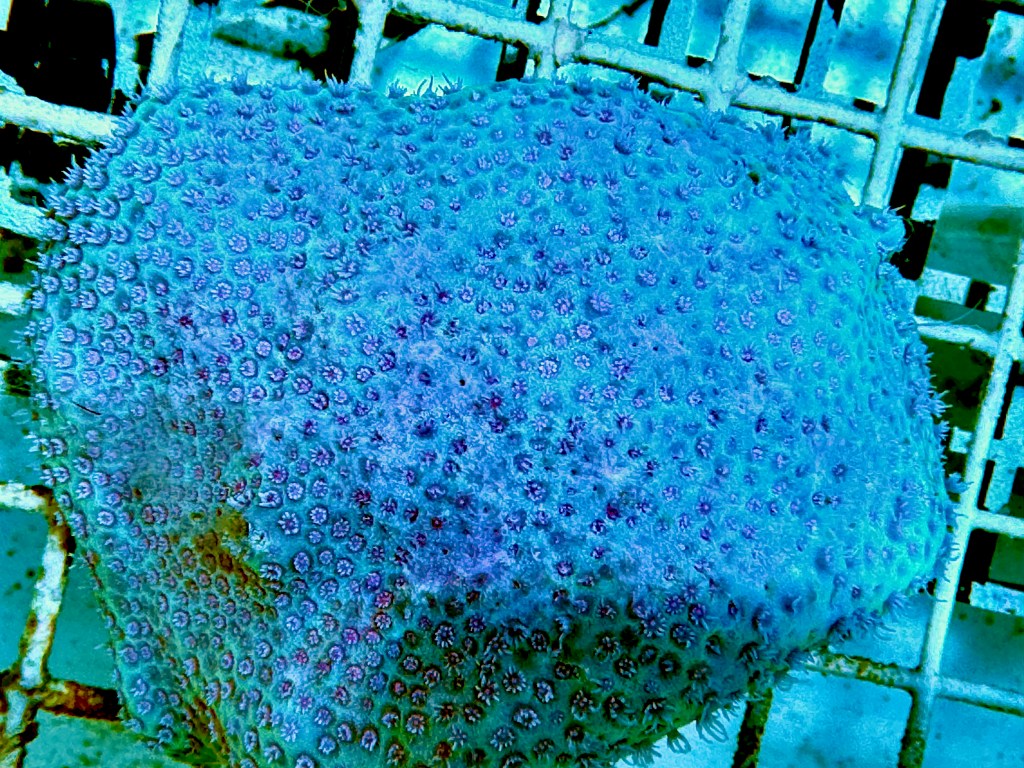

The fifth experiment is running now. It has been the most successful by far, surpassing my previous two week record, and with healthy coral and no water changes.

I have taken all of the lessons learned from previous experiments and used them to hone my technique. Fundamentally, this is the same experiment as the fourth one, except at a slower rate. The electrolysis only turns on for 1 hour a day, 30 minutes at 12 P.M. and 12 A.M.. As a result, over the course of a week, only 1/24 of the harmful compounds are created and less chlorine and sodium (i.e. dissolved salt) is removed from solution than in previous experiments. That could also mean that 1/24 of the benefit will be reaped, but that remains to be seen. So far, the corals have survived for 3 straight weeks, and seem to be in good health. I will update you all more when this I conclude this experiment.

Conclusions

Two years ago, I started this journey hoping to discover why and how quickly electrolysis works to enhance coral growth and resilience I managed to discover many reasons why it won’t work, a fact that discouraged me as my failures mounted. However, I now see what I have actually accomplished. I had made many mistakes, but I fixed them all, and with every experiment I learned more, and made more progress towards success.

Most importantly, because I am publishing this research, those missteps will not be made again, by anyone. If my research had existed two years ago, I could be writing a paper that fully explains how well electrolysis works to enhance coral growth and resiliency in a closed aquarium environment. Alas, these research findings did not exist, but now it does. Maybe (hopefully), it will be me who finishes this work and figures out how to use electrolysis in an aquarium. Either way, in some way, I have helped advance our understanding.

Leave a comment