Year by year, coral reefs dwindle due to environmental degradation including global warming, ocean acidification, eutrophication, and associated diseases. We must take innovative steps to reverse the decline. Fortunately, 47 years ago, MIT graduate Thomas Goreau discovered that coral grows rapidly on the cathode of a low-voltage electrolytic cell and is protected from environmental degradation (Goreau, 2018). Indonesian coral preservationists utilize reef electrolysis to great success, but it’s not widespread in the rest of the world. In Western science, attempts by scientists to successfully prove the technology of using electrolysis to grow coral in a closed environment failed due to problems unrelated to electrolytic cells (Koster, 2017). I have already surpassed their attempts with my previous experiments, and I now intend to prove that electrolysis is a powerful technological solution for coral reef preservation.

My experiment will accomplish three things. First, I will confirm that electrolysis grows coral faster. Second, I will measure how much faster they grow. Most significantly, I will invent a repeatable experimental approach to using coral reef electrolysis in a closed environment. I have many years of experience with complex reef aquariums, and I will scale up the experimental seawater electrolysis system I have built to implement my project proposal.

Idea: Problem

Given the scale of the crisis, the global degradation of reefs requires a comprehensive approach. Existing coral reefs must be protected from further degradation, and dead or dying reefs must be revived. That is very difficult to do as most threats(acidification, warming, and eutrophication) require global cooperation to be addressed.

Currently, the dominant solution to reviving dead or dying reefs is farming coral in the ocean and seeding reefs with that coral. The coral fragments are suspended from strings near the surface, so they get plenty of light and can grow in all directions. As a result, they grow slightly faster than the coral on reefs. It’s an effective strategy, but there are flaws. The coral are grown in traditional reef environments, so are equally vulnerable to eutrophication, acidification, and warming as the reefs they hope to save.

Seawater electrolysis can have a significant impact by improving water chemistry near the cathode to directly and locally protect existing healthy coral reefs from environmental threats. In addition, seawater electrolysis can be used to revive dead reefs by quickly growing a stockpile of corals to be used to reseed them.

Much research needs to be done for electrolysis to help save the reefs. That research is difficult and expensive in open ocean environments, and there is no protocol for electrolysis in a controlled aquarium environment. So far, the lack of a controlled experimental solution has stymied most research on coral reef electrolysis. If my experiment is successful and the electrolysis works as intended, I will have set out a protocol that I can use and future researchers can follow.

Past failed experiments generally demonstrated a fundamental lack of knowledge of the complicated processes required to grow coral in a tank (Koster, 2017). In addition, one of the most difficult additional challenges is that electrolytic cells produce chlorine gas in seawater, and there’s nowhere for that to go in an aquarium. Chlorine is highly toxic to coral, even at low concentrations. These problems must be addressed, too.

Idea: Current work

Understanding the chemistry of low-voltage electrolysis is crucial to predicting how the chemistry of a closed marine aquarium system changes while being electrolyzed. At the anode, toxic gaseous Cl2 and hypochlorous acid (HClO) are produced – significant problems in a closed aquarium system. At the cathode, gaseous H2 and NaOH are produced. The H2 bubbles off and the NaOH increases the concentration of OH- ions, locally increasing the pH – this is the main beneficial purpose of electrolysis. Seawater is a highly buffered solution (need citation), which is why the oceans have been able to absorb massive amounts of atmospheric CO2 with only slightly lower pH, so far. By increasing pH near the cathode, electrolysis increases alkalinity by increasing the concentration of Ca(CO3)2.

Corals require alkalinity for skeletal growth, and aquarist research has shown that higher alkalinities benefit coral growth and health (BRSTV, 2023). In particular, high alkalinity from electrolysis improves corals’ ability to adapt to climate change (Goreau, 2022), particularly acidification (Feng, 2016). Alkalinity is a buffer, so more carbonic acid is required to lower the pH. Ocean acidification is caused by the increase in the concentration of carbonic acid due to higher atmospheric CO2, so raising the local alkalinity of reefs reduces its impact.

Idea: Solution

By inventing a proven experimental apparatus for electrolytically enhancing coral health and growth in a highly controlled environment, I can help unlock further research to advance our understanding of this electrolytic technology for coral preservation. Also, electrolytic coral breeding tanks will allow the rapid reseeding of reefs in the event of bleaching or disease and have major commercial applications. Commercial coral farms could use it to produce stock quickly, reducing coral harvesting from the wild. Finally, by proving the effectiveness and sustainability of electrolytic protection and nourishment of coral, I can encourage large-scale government and NGO interventions using this technology to preserve and expand highly diverse coral reefs well beyond Indonesia’s promising but limited projects.

This project is not simple, and there are good reasons for past failures. However, I have significant practical knowledge from many years of tending to coral reef aquariums in my home. One of the most difficult challenges is that electrolytic cells produce chlorine gas in seawater, and there’s nowhere for that to go in an aquarium. Luckily, I have a proven solution for that problem from my previous experiments: copious amounts of activated carbon to adsorb the chlorine (DeSilva, 2000).

There are many examples of successful coral reef electrolysis in the ocean, especially in Indonesia, but no one else successfully uses electrolysis in reef aquariums. So, I will not be improving on the current technology, as there is none. Hopefully, I will be standardizing it. It might be hard to convince people to try out electrolysis if what they are already doing is working according to current standards. If this experiment is a success, and I prove that electrolysis can grow coral 2-3 times faster, then no other coral-growing methods come close.

Plan: Approach

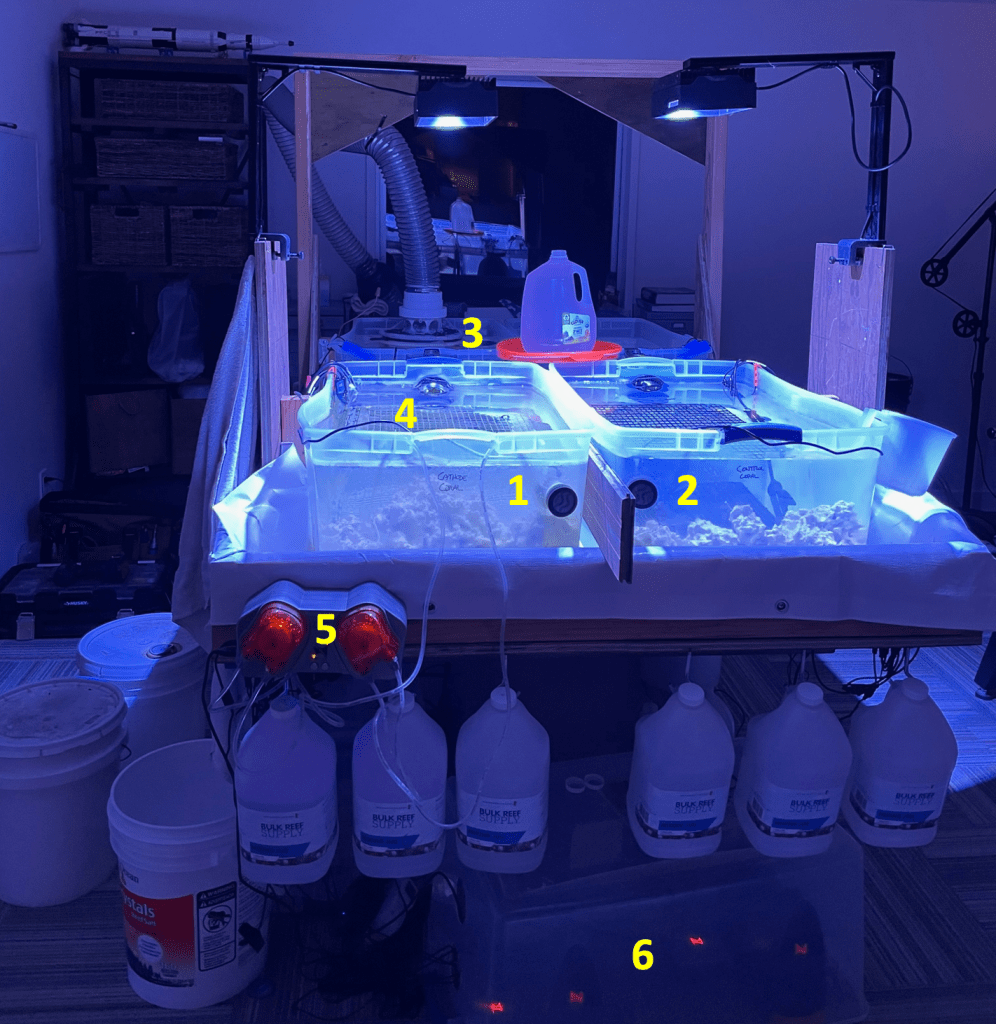

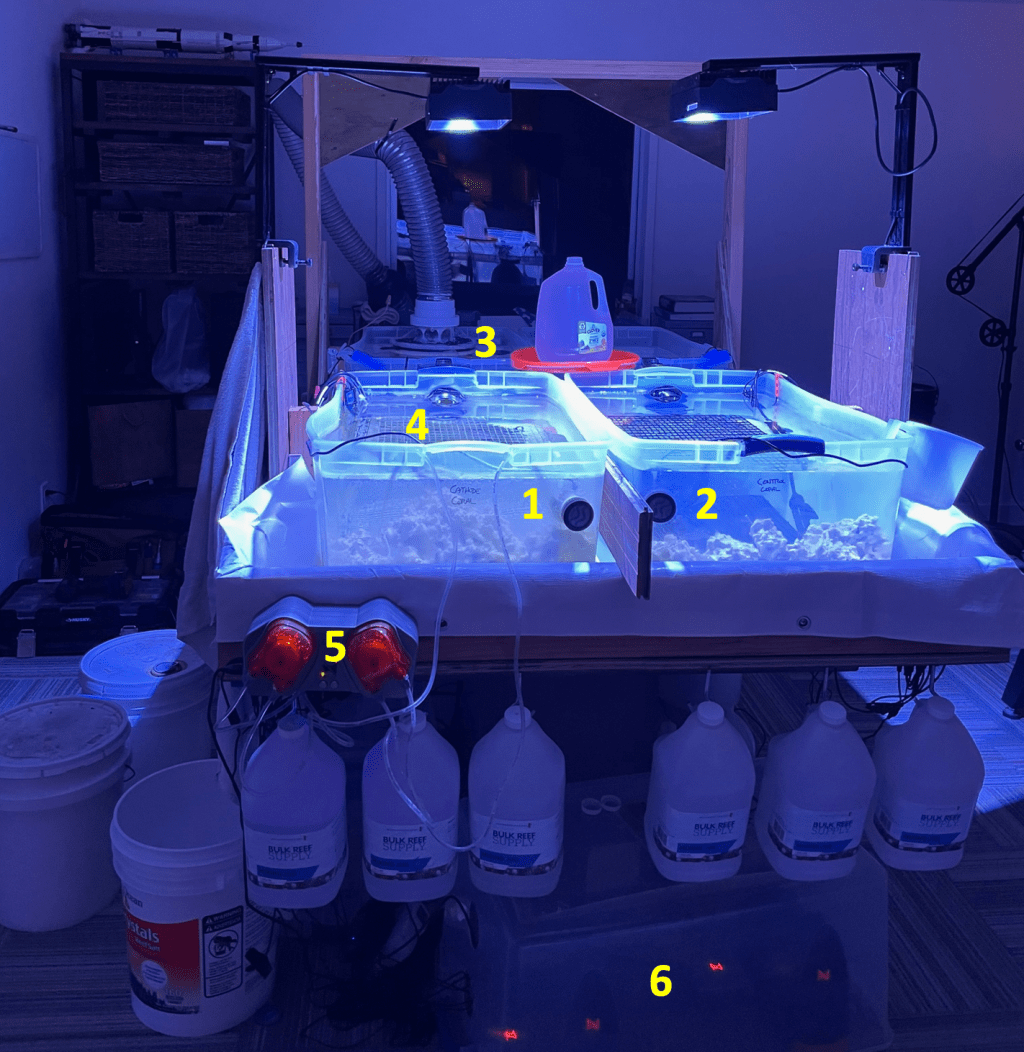

My proposed project uses many resources I already have. I have set up two custom-built 50-gallon tanks with heaters, filters, circulation pumps and coral-growing lights. Each tank is composed of two 25-gallon containers connected with two 3-inch PVC pipes with ball valves. The anode side of the experimental tank has a ruthenium-oxide-coated titanium anode placed in a perforated 1-gallon bucket lined with 2 inches of activated carbon granules(4.7 kg) and capped by negative pressure ventilation. The cathode side has a stainless steel wire mesh cathode; that mesh is where the corals will be placed. I have already set up Apex Trident titration colorimeter measuring systems to track temperature, pH, alkalinity, calcium and magnesium levels in the tanks; Apex Dos systems to automatically maintain alkalinity, calcium and magnesium levels as those chemicals are consumed by electrolysis and coral growth; and Apex Jr controllers to automate testing, measurement recording and dosing. I also have testing reagents, activated charcoal, reef salt, micronutrients for the coral and reverse-osmosis deionizationon (RODI) filters to create the nearly pure H2O required by marine aquariums. I will use a low-voltage power supply to run the experiment at approximately 5 volts and 0.5 amps to approximate the cathode electron density of the larger-scale electrolytic cells used in Indonesia.

While electrolysis is happening, overall alkalinity drops as calcium carbonate accretes on the cathode. This is not a problem in the ocean since seawater constantly flows over reefs. To keep the water chemistry stable in the closed aquarium system, I am automatically dosing soda ash to bring the alkalinity up. I am experimenting to find the exact amount of soda ash mixture that needs to be dosed daily, working towards an equation for that number that scales with the amperage. Altogether, this should result in the tank chemistry remaining stable while electrolysis is running.

Once I have stabilized the water chemistry, I will add seven types of coral to the tanks and observe their health during the course of the experiment, taking photographs, measuring and weighing the coral, and tracking added minerals and changes in water chemistry.

Plan: Resources

I have been working towards the goal of running this experiment for about 8 months. I have completely built my experimental setup and conducted preliminary experiments to determine its feasibility. At this point, I require coral fragments (frags) for the experiment and mentoring to help with the experimental analysis and future plans.

I will use a total of seven different coral species, with two samples of each in either tank: Montipora capricornis, Seriatopora hystrix, Poccilopora damicornis, Leptoseris sp., Stylophora pistillata, Psammocra sp., and Acropora cervicornis. I will only use hard corals (which accrete CaCO2) for the experiment. Specifically, I want to use SPS (small polyp stony) coral frags, which are the reef builders and most crucial to the reef environment. I will acquire the corals from online sources that I have used in the past and know to be reputable: https://www.thecoralfarm.com/#/.

I am already being mentored by my Advanced Biology teacher, Emily Willingham, and have established a relationship with the head of the California Academy of Sciences’s aquarium, Bart Shepard. Although Emily is a published PhD research scientist and has been helpful, she is not a marine biologist, so hasn’t been able to help with my experimental setup. As a result, the design of my experiment is entirely my own and could be improved with the help of a mentor. Additionally, the analysis of my data will be completely up to me, and I would really like to have a professional marine biologist or researcher help with that.

Plan: Project Goals

My project has three goals:

- Keep the seawater chemistry stable during electrolysis in a closed aquarium.

- Measure how much faster and cost-effectively coral grows in electrolytic cells.

- Publish my approach and results for the world to use.

I have already made progress on the first goal – I keep chemistry stable with automatic dosing, which works but needs fine-tuning.

Regarding my second goal, if the evidence from Indonesia is true, I can expect 3-4 times faster growth in the electrolytic cell. I also plan to estimate the cost-to-growth ratio of electrolysis for use in coral farms. For example, if electrolysis is 50% more expensive, but corals grow 3 times as quickly, the extra cost is worth it. Finding that ratio is key to pitching electrolysis to coral preservationists and convincing the government to invest in electrolysis to save the reefs.

As for my third goal, I am documenting my progress on my blog at www.resilientreefresearch.org and on Instagram @resilientreefresearch. I self-published my initial experimental proposal and ocean-based experimental process, and documented my build steps. I will also publish my experimental results in a research paper.

Plan: Future Goals

Once I have proven that coral grows more rapidly in this controlled environment, I can test how electrolysis protects coral health. I can run experiments where I increase the temperature, acidity and nutrient load separately and in combination to understand how electrolysis protects coral from environmental degradation. Such tests are impossible to perform in a repeatable and controlled way on natural coral reefs.

Finally, there is evidence that in-place electrolytic generation of calcium carbonate minerals (e.g. limestone) on ocean reefs could be a scalable and cost-effective means of permanent carbon capture (La Plante, 2021). While this is not a primary focus of my project, it would be interesting to talk with mentors to explore that side benefit as well.

Plan: Risks

The primary risk is that corals are very finicky and difficult to grow in aquariums without introducing electrolysis. There is a chance the experiment fails because of something completely random, like disease or pest invertebrates. To prevent the introduction of pests and disease, I will dip each coral in an iodine solution, as well as CoralRX.

I have solved the chlorine issue, but it could still harm the tank. Activated carbon can absorb its weight in chlorine gas, but once it’s reached that point, any chlorine produced will go straight into the water and kill the coral. The carbon adsorption will last for 3.8 months at 0.5 amps, much longer than needed.

Plan: Timeline

- The experiment will begin by preparing the tanks, weighing and photographing the corals, and placing the corals in the tanks..

- Automated measurements of key water parameters will begin. I will track alkalinity four times daily and calcium and magnesium levels twice daily. The Apexes will also continuously record pH, temperature and added mineral solutions.

- After 2 weeks, the first growth data will be recorded, and every two weeks thereafter for as long as the experiment runs.

Personal: Interest

My personal interest in marine sciences stems from my aquarium hobby. I started my first aquarium in 2019 and set up my first reef tank in December 2020. That 50-gallon reef tank is still up and running, but a bacterial bloom wiped out all of my initial fish. They have since been replaced. A year later, I set up a 265-gallon tank, focusing on fish rather than coral. That tank is thriving, and we have kept many difficult fish alive for over 2 years. My favorites in that tank are the Quoyi parrotfish, yellowhead butterflyfish, and Asfur angelfish. I am also an avid snorkeler, and SCUBA diver, with over 50 completed dives and several advanced certifications. In all my dives, I see the devastating impact of climate change. Seeing that destruction firsthand motivated me to make a difference. Following that motivation led me to create this research project, which I hope will help those reefs someday.

Personal: Qualifications

My four years of experience with aquariums, including complex coral reef aquariums, have prepared me to take care of the corals I will need. I know what parameters must be monitored carefully and how much light each species requires. I know how to conduct the tests to monitor the most important parts of the tank’s chemistry and what to do with that information. Additionally, the 7 months of research I have done so far have educated me on the electrochemistry involved. I understand how the flow of electrons disrupts natural saltwater chemistry.

I am an avid STEM student and have done well in my classes. This year was the first time I could choose my own classes, and I took advantage of it by taking Advanced Biology (AP equivalent with labs) and Environmental Science. I am an Advanced certified scuba diver. I have taken many summer courses on marine biology, including a 2-week Seaquest program which I graduated with high honors, a 3-week marine biology course on Curaçao where I got certified in coral restoration and a 2-week course on marine biodiversity and conservation at Salish Sea Sciences in the San Juan islands in Washington.

References

DeSilva, F. (2000, January). Activated Carbon Filtration. Water Treatment Guide. Retrieved December 29, 2023, from https://www.watertreatmentguide.com/activated_carbon_filtration.htm

Feng, E. Y., Keller, D. P., Koeve, W., & Oschlies, A. (2016). Could artificial ocean alkalinization protect tropical coral ecosystems from ocean acidification? Environmental Research Letters, 11(7), 074008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/7/074008

Goreau, T. (2018, January 12). Electrical Stimulation Greatly Increases Settlement, Growth, Survival, and Stress Resistance of Marine Organisms. Global Coral Reef Alliance. Retrieved December 29, 2023, from https://www.globalcoral.org/electrical-stimulation-greatly-increases-settlement-growth-survival-stress-resistance-marine-organisms/

Goreau, T. J. (2023). Perspective Chapter: Electric Reefs Enhance Coral Climate Change Adaptation. In IntechOpen eBooks. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.107273

La Plante, E. C., Simonetti, D. A., Wang, J., Alturki, A., Chen, X., Jassby, D., & Sant, G. (2021). Saline Water-Based Mineralization Pathway for Gigatonne-Scale CO2 Management. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 9(3), 1073–1089. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c08561

Supply, B. R. (2023, October 9). Elevated alkalinity and calcium for faster growth? Part 2 – BRSTV investigates. Bulk Reef Supply. https://www.bulkreefsupply.com/content/post/elevated-alkalinity-and-calcium-for-faster-growth-part-2-brstv-investigatesW. Koster, J. (2017). Electrolysis, halogen oxidizing agents and reef restoration [MA thesis]. University of California Santa Cruz.

Leave a comment